He does the monster mash

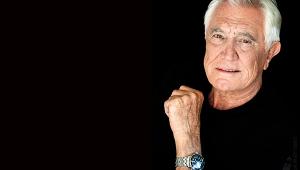

Having begun his animation career at Pixar working on Toy Story and THX promos, Hal Hickel transfered to Industrial Light & Magic in order to work on the Star Wars prequels having been a fan of the franchise since childhood (he even submitted his own script for a Star Wars sequel at the age of 12 and received a polite rejection letter from producer Gary Kurtz). Since then he has worked on a variety of blockbusters including Star Wars: Episodes I and II, first three Pirates of the Caribbean films, Iron Man and Super 8. His most recent role was as animation supervisor on Guillermo del Toro's sci-fi blockbuster Pacific Rim.

HCC's Anton van Beek caught up with Hickel to discuss the challenges of animating giant robots, 3D conversion and the importance of giving monsters personalities...

What does the job of animation supervisor on a movie like Pacific Rim entail?

‘Every visual effects project that Industrial Light & Magic works on has a visual effects supervisor who’s sort of our overall creative lead. But any project that we work on that has any kind of character animation, be it giant robots or Yoda, will have an animation supervisor like myself who oversees the character animation, and works with the director creating the characters and so forth.’

Guillermo Del Toro comes across as a very collaborative person to work with. Was that the case on this movie?

‘Generally you get two types of directors. There are those that have a very clear vision of where they’re going, and in some cases that may make them a little less collaborative, as they’re more looking for you to just execute their vision. At the other end of the scale you may have a director who is not so visual and doesn’t have a clear vision of where they’re headed, but who brings other things to the table and is really collaborative – which is fun.

‘Guillermo is the sweet spot in between. He’s got a very clear vision, he draws well and he can explain the image that he’s looking for or the moment, the feeling. But at the same time he’s highly collaborative. He expected us to contribute ideas and test things out that weren’t in the plan to begin with.'

That must be a great experience compared to creating exactly what has been storyboarded...

‘Absolutely. Frequently in visual effects, we’ll work with the director ahead of shooting, and be on set during the shooting of the footage that we’re going to be putting our creatures into. But at the end of the day they’ll give us a cut scene, which is a pretty tight framework for where your creature goes. And they’ll say: "Okay, there are the extras running way from your creature, so it has to go here and get from A to B in so many frames." Whereas, on this film, because the action is taking place on such a vast stage, it really didn’t make sense to shoot footage to put the Jaegers and the Kaiju into. Even in the case of the Hong Kong fight, there really weren’t any streets wide enough to stage that action, so that all had to be synthetic.

'What that meant is that the workflow became more like an animated feature. Rather than being given footage into which we’d put our creatures, we were just given storyboards and animatics and then would make a crude run-through in CG to figure out all of the staging, and then hand that off to the animators. This meant we had a lot more freedom to design shots and to figure out how to shoot things. So when we got to the performances of the creatures in the shots we had a lot more freedom.’

Were you already a fan of the Japanese Kaiju genre that Pacific Rim draws upon?

‘I was a huge fan as a kid. I think the first film to really make an impact on me, in terms of what I ended up doing later, was the original King Kong. I saw that on TV and quickly after that, on any Sunday in the ‘70s, you would find me watching Godzilla, Gamera, Rodan or any of the big Japanese monster movies.’

When dealing with these kind of creatures you’re working on an incredibly large scale. Does that pose any problems?

‘One of the challenges is that immediately when we get a project we start looking around for references that will put us in mind of what we’re doing. So, for a dinosaur picture you go to the zoo and look at giraffes, rhinos and ostriches for movement references. But for things that are 250ft tall there’s nothing out there. Okay, there’s a giant earth-moving machine in Germany that’s on that scale, but it doesn’t walk!

‘We already know some of the rules for how to make big things move, such as slowing them down – but the difficulty there is that almost all of our scenes with the Jaegers and the Kaiju were action scenes. They’re fighting scenes, so you couldn’t have that transpiring in what appears to be slow-motion. You would have to find ways to keep the scale correct, but still have it be exciting – figuring out how fast we could move them and still have it be real. We also had to be mindful that surrounding them at all times there was going to be realistic fluid simulations when they’re in the ocean, or destruction simulation of them knocking down buildings…’

Exactly! You’re surrounding them with incredibly complex environmental and particle effects as well...

‘Yeah, one of the largest challenges on this movie was the destruction and water simulation. That stuff evolves every year and gets better, but it’s still some of the hardest and most challenging work there is. If we move the characters too fast it’ll make the water and destruction simulations blow up, look crazy, and there’s a visual mismatch between the two. So when animating the characters we had to be mindful of what was going to follow on after in the animation.

‘Once we’d reached the point where it was about as fast as we could go but still looking good, it became a job of discovering how to shoot the action to keep it feeling exciting. Where to cut from one shot to another, inventing shots. As I said, a lot of that is down to Guillermo. He had a very strong vision for the film and worked closely with his editors, but he did invite us to contribute.

‘For instance, in one of the first fights between Gipsy Danger and Knifehead, there’s a moment where Gipsy throws this big punch. Now, rather than play that wide as just a big sweeping roundhouse, which would look quite slow, we came up with a shot where the camera is actually mounted on Gipsy’s fist. So you’re hurtling through air towards the Kaiju’s face. That’s an example of the way that we can inject some excitement into what otherwise might be the slow process of getting that fist over to the Kaiju.’

The Kaiju have to be given a sense of intelligence purely through the animation. How difficult was that to pull off?

‘Well, monsters are Guillermo’s favourite thing. He loves designing giant robots, but at the end of the day he really loves his monsters.

‘One of the things he was adamant about from day one was that he never wanted them just standing there looking, well, monstery. It always had to look like they were thinking, planning their next move or recovering from a punch or something. We could never just have them waiting for the next punch to land, as you might find with a stunt person. He was always saying, “Yeah, it looks cool, but what is he thinking, why is he doing that?” That was great, making sure that there was always motivation in what they were doing.

‘It was also very important to him that all of the Jaegers had their own personalities and all of the Kaijus had their own personalities. So Knifehead is very different from Otachi who is very different from Scunner. They all had their own capabilities and wildly different designs and personalities.’

Del Toro has a fondness for asymmetrical creatures. That’s evident here in the three-armed Crimson Typhoon Jaeger. Was that tricky to design?

‘I’m just glad he didn’t make any three-legged Jaegers! It’s really hard to animate a walk with three legs and there’s a good reason why there aren’t any animals on our planet that have three legs. But, yeah, he does like that – asymmetry in general just gives extra visual interest. In the case of Crimson Typhoon it wasn’t a huge challenge because the arm was just a great opportunity to do something different. I think the biggest challenge with Crimson were actually the buzz-saw hands, because that wasn’t built into the design right from day one, it was added a little later by Guillermo during the storyboarding process. Then it fell to us to take a look at the hands and figure out how they could plausibly split apart and turn into these spinning saws.’

How many VFX shots did your team complete for the film?

‘Around 1,600. I don’t have the exact number in front of me, but I know it’s around there. And that was about 18 months work. Some of us were on the project for almost exactly two years, if you go back to the test sequence we did of about five shots, which was before we’d actually been awarded the work.'

The live-action material was converted to 3D in post, but the VFX was completed in native stereo. Did that affect how you worked?

‘We did our all-CG sequences natively, although there were also some visual effects sequences that were largely plate-based that were converted. I would say that the biggest challenge, frankly, was that decision to go 3D was made kind of late in the process. If it had been made earlier, it would have been easier.

‘One of the big concerns we had going into the 3D is that when it’s not done right 3D can often miniaturise large scenes. Say you go outside and shoot a cityscape of skyscrapers in 3D – it’s not going to have a lot of depth unless a seagull flies by close to camera, because all of that stuff is in the background and distant from the camera. For that reason we were concerned that there might be an effort during the 3D process to force the sense of depth, and that could miniaturise the action. But Guillermo had a really good eye for it, embraced it, got excited about it, and the results were good. I think they really look beautiful and it didn’t harm the action.’

One of the hot topics linked to 3D right now is 48fps HFR filmmaking, as seen on The Hobbit...

‘I think it’s interesting. It solves a lot of visual artefacts to do with strobing and so forth. I think the difficulty is that many of those visual artefacts are things that people have just grown up with and that they view as being integral to the film experience. So when you smooth them out they feel like they’re watching something else.

‘It’s like digital projection. When that came out you used to hear a lot of people, film buffs, saying that it was too smooth, it didn’t feel like film, that there was no gate weave or scratches or anything that makes it feel like they were watching it on celluloid. And that sort of went away. Not too many people any more are bothered by seeing a film projected digitally. In fact, these days when I see a movie projected on film, it’s glaring to me when I see a hair or a spot of dirt.

‘So I wonder if, over time, people will just get used to seeing a smoother, less stroboscopic image. And in a while kids will grow up on movies like that and think that’s how movies should look. But I don’t really have an opinion either way. It does look a bit weird to me, but I understand why it looks weird and that my eyes aren’t used to it.'

Finally, what kind of movies do you like to relax with at home?

‘There’s a handful of movies that are always at the top of my list. One of them is Chinatown; I dearly love that film and have watched it over and over. And then there are movies you’d sort of expect: Blade Runner, Metropolis, King Kong, anything by Ray Harryhausen.

‘Lawrence of Arabia is another favourite. My son is 12 now so I’m starting to get him in front of movies, and he’s been great about it. It can be tough sometimes with kids and older films that aren’t paced as quickly as modern ones, but he’s really receptive so it’s a lot of fun.’

Pacific Rim is available to buy now on DVD, Blu-ray and 3D Blu-ray, courtesy of Warner Home Video.

|

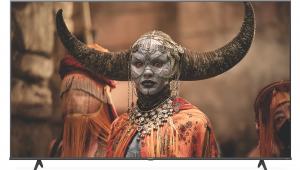

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|