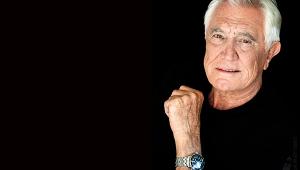

Interview with Dennis Sands – Hollywood music royalty!

Oscar-nominated music scoring mixer Dennis Sands, whose most recent films include Ready Player One and Avengers: Infinity War, talks to Martin Dew about bringing music to movies, the benefits of object-based audio, Marvel's security precautions and his love of PMC loudspeakers...

First: can you explain the role of a music scoring mixer?

Basically, it's quite a big job, and the first part of it is starting a conversation with a composer. I find out what the scope of the score is, what the composer has in mind, what the construction of the score is. Is it all orchestral, or acoustic, are there electronics involved, or is it primarily electronic? Or is it a hybrid score, both electronics and orchestra? Are there any specialised instruments? For example, is it a solo piano-driven score, or are there other instruments that need to be isolated, or treated in a certain way?

So I'll get a real concept of what the score is. I'll ask for demos of the cues themselves, and quite often – in fact, almost always now – composers mock up their scores for the director to put in; he or she will send this music to the director who puts it in in the editing room, so they can get a sense of what the score is. They'll listen to each cue to approve or ask for changes, and to see how it works in the movie.

I get a sense of what the score is, and from there I conceptualize how I want to set up the studio; it's my responsibility to determine what the setup is on the scoring stage, or in the recording studio. I have to describe the setup, but also what microphones I'll use, other electronics, how I want them plugged in, if there's any other outboard equipment like compressors, limiters, reverbs, that kind of thing. All that's done for the recording phase.

While the recording is being done, I'm in the control room listening, obviously. I'm very involved in the dynamics or the performance – which I guess is a better way of putting it – of the music. For example, if I hear there's a particular cue being recorded, and everyone's recording live, and the trumpets are really loud in relation to everything else, I'll ask for a dynamic change and have the trumpets play less, or if there's some big instrument like taiko drums in the percussion – and it's just overwhelming everything else – I'll suggest that we record that separately. It's things like that, which I know are going to be an issue later on in the mix or in the dub.

Does that make you effectively the 'music producer' for the movie?

In a way. I have so much experience now of doing this that I can look at the picture and I can almost hear what it's going to sound like in the final dub, even though when we're scoring generally we're looking at the picture, but not hearing any other sound.

Occasionally we'll play music back against the dialogue, and that's all there is, so rarely do we have any sound effects playing along with it. Let's say there's an exterior street scene and there are people talking and maybe whispering to each other, and there's very light strings playing underneath it. I know that if we hear any street ambience, that music is going to disappear, so I'll recommend to the composer that we need to get a little more sound out of the strings. They can't play quite so softly, otherwise it's just going to disappear in the final dub.

Things like that are important to guide the recording process. Once it's done, there's not much you can do outside of adding electronic samples, which would change the sonic quality of it.

All this is part of my responsibility as a scoring mixer – in the recording process. The mixing process is a whole other thing. Here my responsibility is to achieve a good balance between, say, orchestra and electronics. It took quite a bit of time to learn how to do that, because the issue of balancing electronic with acoustic instruments, especially an orchestra, is that electronics typically have a lot of presence to them and if they're too loud against the orchestra, the orchestra will sound small. It won't have any impact. To get the balance of the two is challenging.

Do you talk to the composer a lot?

Quite a bit, especially in the recording process. It's very popular these days to record in what we call 'stripes' – doing separation. Let's say we start with strings and woodwinds, and maybe harp, and then we'll add brass, and then we'll add percussion to that… These are all recorded separately.

The positive side of doing that is that it gives you control of those separate elements. The negative side of it is that there are often intonation problems, so the tuning of, let's say, the brass against the strings can be a real issue. Also, the timing is more challenging for the musicians in order to get everything in sync, so very often after we're done recording, we have to edit the various elements together so that they fit together rhythmically. So, there's positive and negative.

Also, the dynamics are different, and just sonically it's different. For me, personally, I much prefer the sound of all the instruments recorded together. Also, for musicians, especially orchestral musicians, they learn how to play their instruments sitting with everybody else. They adjust their intonation and dynamics and performance based on hearing everyone else in the room together.

When you now take that apart, and you separate them out, and their reference is headphones, which is a much different experience, it's challenging for musicians. It really is.

Do you have a background in classical music?

Well, I didn't study formally. I've been a fan of music in general all my life. I grew up with rock and pop, but I always loved jazz, and I really enjoy classical music, and listen to every kind of music now.

I enjoy listening to a lot of hip-hop and pop music because there are a lot of interesting sounds; the way certain reverbs and effects are used. I steal some of that, if you will, for hybrid scores, to help create a sonic environment.

But with classical music, you hear composers reference a lot of other classical composers in their scores. One of the obvious ones is Aaron Copland in Western-type scores, or that sort of sweeping visual genre.

There are many others as well, certainly Mozart, Beethoven and Bach and so on. You can hear elements of those composers in many, many film scores, not just contemporary ones, but older ones. It's not in any way uncommon for those great classical composers, their concepts and visions, to be integrated into film scores.

Has the development of 3D audio – Dolby Atmos and DTS:X – and before that, 7.1 and 5.1, changed your approach to mixing?

Absolutely, it's changed it a great deal. Let's talk about the history and evolution, at least from my perspective. I've been doing this for a long time, so when I started out movies were mono. That was it. And also you had to deal with that awful Academy filter, or curve, which was brute force noise reduction. They just basically filtered out all the high frequencies and low frequencies, and you had this sort of midrange thing. It was okay for dialogue and sound effects, but it absolutely killed music.

Then when Ray Dolby came along and introduced matrixed four-channel surround, and in conjunction with that he had this noise reduction system, it just revolutionised mixing. Again, it was most favourable for music. You suddenly had full dynamic range and frequency response. And then it went to digital.

There were inherent problems with the matrix system – it was wonderful for frequency response, but it was hard to control channel placement. Let's say you'd have a stereo synthesized pad. What happened is, depending on the frequency content, it would just sort of move around. Maybe you'd want to place it left and right in the front monitors, and what would happen is that a lot of it would end up in the surrounds. When 5.1 discrete digital was introduced it was a miraculous step for us, because then with all of our assignments we could absolutely control everything. Nothing moved around, they were all discrete channels. Plus, we had this LFE channel, as an added plus. That was a great thing, and that changed mixing completely.

And then 7.1 came along, and instead of just a stereo surround channel, we had four channels of surround. Each format has changed mixing for everybody. And each step, sonically for films, and how they translate to home theatres, has gotten better and better.

With object-based audio, are you sending music up to the ceiling?

I do occasionally. There are some aspects where it's really great. I look at the ceiling channels as I look at the subwoofer. If you use it occasionally, it's very effective, and it's a really interesting additional added aspect, but if it's constant, it sort of disappears.

I've experimented with it a lot. If I have, let's say, overall microphones which I record with an orchestra, and place them up on the ceiling, so the entire time the orchestra's playing I also have these ceiling channels playing, it tends to actually mono out the orchestra. It sounds smaller.

But I found that if I use them occasionally, it's very effective. So, what I like to do is, if I have a choir, I like to move it up towards the ceiling. It separates just a little bit, but it gives it a wonderful ambience. Again, if it's used occasionally, to me anyway, it's a wonderful effect. It becomes more interesting.

It's the same thing with a subwoofer. If you hear it every once in a while, it has a great deal of impact and it's fun and interesting, and feels very cinematic. The same thing with sound effects or anything – if it becomes constant, then it's just like wallpaper.

The definition is amazing in these object-based, 3D formats. Atmos, which I have most experience with, is quite stunning, actually. But let me say one thing: not every director loves Atmos. I work with a couple who feel that everything should be up on the screen. They're not enthralled with so much sonic information going into the surrounds. Other directors absolutely love it and want as much of it as possible. It's a sensibility, it's whatever that taste or sense is for each director. Like anything, it's not for everybody.

You could say the same thing about 3D imagery. Personally, I love it for certain kinds of projects. It was fantastic for Gravity and Avatar, movies where it's really meaningful. But not for every single movie. Maybe you could say the same about Atmos.

Looking at your list of credits, you keep getting asked back by the same directors. There's the Robert Zemeckis/Alan Silvestri combo, and Sam Mendes/Thomas Newman...

Both of those are great composers. They're filmmakers, really. They understand the language. So much of their job is to have a conversation with the director, understand what the director wants to do, the emotion that the director's trying to portray, and interpret that musically. That's a part of their job, and they're both great at that.

And they request you to be part of that team…

Gratefully, they do. I met Alan when we worked on the TV show CHiPs. It was a weekly show and basically the concept was these guys riding on motorcycles, finding bad guys, and what really drove the show was the music.

I had a studio in Hollywood at the time, and we were in the first really contemporary recording studio to be available for film/TV work in L.A. At the time, all the film studios were kind of antiquated. They didn't have modern equipment and couldn't create the kind of sound we wanted. This show wanted a contemporary sound. Anyway, I met Alan and we hit it off and have been working together ever since.

Then in 1984, Alan met Bob Zemeckis. Bob was doing this movie and there were two composers hired, and they just didn't work out. Bob was looking for somebody. The music editor at the time called Alan and said, 'Look, I'm working on this movie, and the director's not happy. If you put a demo together, send it over to me, I'll play it.'

The movie was Romancing the Stone. Alan got the call at like 9am, put something together, made a cassette and sent it over. Bob heard it and loved it, and said, 'I want to meet this guy.' And then Alan dragged me along.

Alan is not only the composer. Bob shows Alan the movie very early in the process, and they talk about it and go back and forth. So, you know, it's a great relationship those two guys have. Alan's really part of the filmmaking process.

Onto hardware. You're now using PMC's MB3-A speakers...

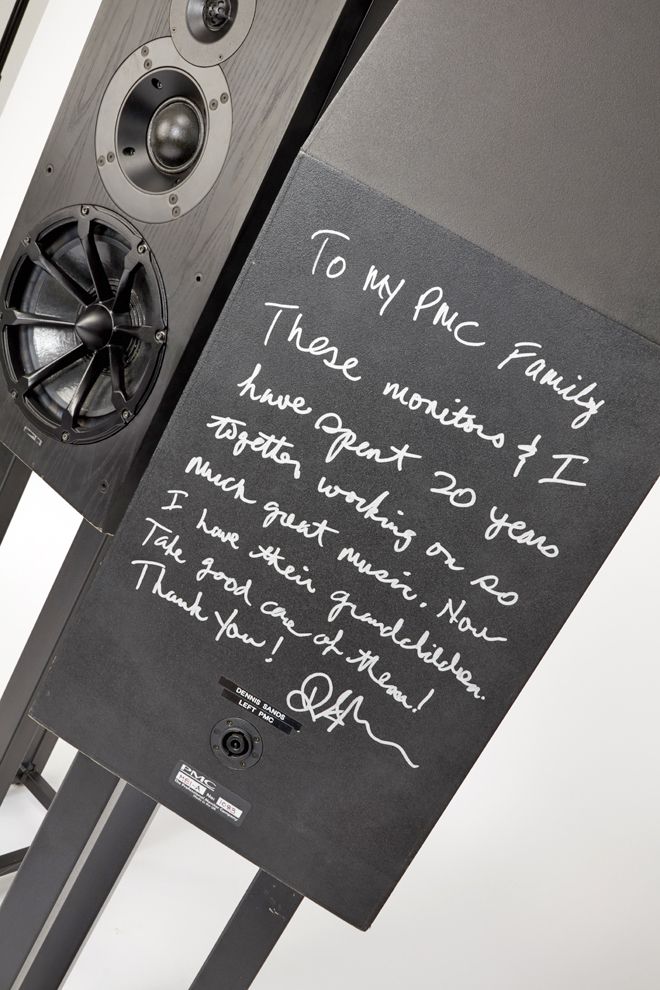

Yes, I've used PMCs for a long time. Twenty years, maybe. I know I mixed even Forrest Gump and Spider-Man and a bunch of movies on those monitors. And then recently, just last year, I got the new MB3-As and Maurice [Patist, President Sales & Marketing USA, PMC] took my MB1s back and wants to put them in his museum!

I really like them a lot. I find they translate very well, first of all, but also they're very realistic, and they can be very unforgiving. So, if I have any issues with anything, I'll hear it right away. If it sounds good, I'll know it. If it sounds bad, or if there's a problem, or if I need to adjust something, I'll know it. They're very definitive and the soundscape is big, and there's a lot of depth to them. I'm very comfortable with them.

Do you have a set at home or do you use them in your studio?

They're in my studio. I use them as a home theatre reference. If I'm doing television or non-theatrical type projects for stereo mixes, doing soundtracks, and I'm going back and forth… I have a large film chain in my studio, so I actually have four monitor systems that I use, but these I use in my studio.

Do you monitor in different-sized rooms, so you know how a score will sound in various environments?

I'm primarily at my studio for mixing. If I'm recording, I'm at different studios, some in L.A., some in Europe. But for mixing purposes, in my studio, I have basically two systems that I use. I have the large film chain, and the PMC system, and they're both great. The PMC setup is full-range. I specifically want them for that purpose. I want the full-range aspect. That gives me a different kind of information from a film system which is not full-range. The film chain has the X-Curve built in, whereas the PMCs are basically flat, which I like also.

When you're listening to the PMCs, you're thinking about how it's going to sound in the home?

Yes, primarily. If it's a TV show, quite often television is mixed now in 5.1. And home Atmos is now gaining popularity and ultimately that's probably going to be one of the primary formats for the home.

What technologies and equipment do you use in the mixing suite?

I use a combination of analogue and digital. The storage format, if you will, is digital.

All studios are so frightened of piracy that security is a huge issue. So, for example, I've been working on the Avengers movie [Avengers: Infinity War], and Marvel Studios is by far the most... 'protective' of its assets. It sent one of its IT guys to my studio. We walked through the studio and he pointed out, 'We'll need you to do this and this and this and this.'

I have a very high-end firewall in my studio and it's monitored 24/7 by a company that sees the traffic in and out, and notices if there's, let's say, an odd address trying to get through. They won't be able to get in, but it will also notify the authorities, the FBI, for example. So, it's a protected system.

Secondly, all my systems are completely disconnected from the internet on my Pro Tools systems. There's no access in or out. And then the picture resides on an encrypted hard drive. When I'm done each night, the hard drive goes into a safe. So there's a lot of security!

When talking about Ready Player One and Avengers, they're all recorded digitally at 192kHz, so it's a very high sample. But interestingly, in the music world, it's still very analogue. It's analogue consoles that it's recorded on, and the microphones essentially are analogue. They go through analogue pre-amps, and it's converted to a digital format and stored on Pro Tools systems.

Prior to us all using Pro Tools, we recorded on analogue tape. And typically an orchestra, every piece of music, would be on two 24-track machines. So you had two two-inch reels, running simultaneously, which would record about 15 minutes or so end-to-end on each reel. We had these huge stacks of tape. It's heavy, it's big and bulky. Avengers was recorded in London and mixed in my studio, and all that tape would have had to be shipped. Now, basically, all these digital files are essentially e-mailed to us. They're uploaded and we download them from the server, and we get it the same day, as opposed to a week later. That's a huge advantage. Plus, you don't need to make back-ups. Everything is a digital copy, there's no generation loss.

What's your favourite film score?

Oh boy! That's a tough question.

I've been lucky – I've worked on a number of great ones. You know, like I said, Romancing the Stone was so important to me personally and professionally. Back to the Future… There are some with Thomas Newman that are great, and some with Danny Elfman that are great.

There's a score with Danny Elfman that I worked on, where the movie wasn't a huge hit, and it should have been – Big Fish, which has an amazing score. Spider-Man was another great score he did. Obviously, Tom Newman's scores for American Beauty and The Shawshank Redemption...

And like I said, with Alan, there's been so many. Just recently I worked on Ready Player One and Avengers: Infinity War. You know, to pick one – and I'm not trying to be evasive – honestly it's an impossible question to answer.

And by the way, you talk about great scores… what about the iconic scores? What about the score of Jaws?

Jaws has so many layers – it's not just the der-dum-der-dum – it's the symphonic passages, the chases…

Absolutely, it's a real demonstration of the power of music in movies... you listen to just two bars. People don't necessarily need to know anything about film music or music in general, but when they hear that, they think of the movie and they're afraid to go in the ocean. It scares them in a fun way, not in a terrifying ‘I need to hide under the couch’ way. You know, they think of the movie. It’s really powerful.

Some argue that film scores are getting less memorable. People can hum Star Wars, but not Avengers. You don't come out of the cinema whistling the tunes…

I would tend to agree with that. Listen, it's up to the director to want a memorable or melodic score. For some reason, the trend is away from melody, and towards almost sound design. It's hard to differentiate the music score from the sound design. That, to me, is diminishing the power and the opportunity that a film score can present.

Nobody ever leaves a theatre humming the sound design, but a great melody stays with you, and it reminds you of the movie, that experience. When a film score moves away from a melodic component, it certainly becomes less memorable. A drum loop, no matter how great it may be, isn't memorable – you'll hear it and it's hard to differentiate it from anything else.

By the way, Avengers does have a nice melody. Alan Silvestri wrote the very first one. He's very melody-oriented, as you know. Back to the Future is another of his greats, and certainly there's been others – Forrest Gump, talk about an amazing melody! Probably a lot of people remember where they were when they first saw that movie. It had that kind of impact and certainly the melody, the theme, is so reminiscent of that.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|