Exclusive Interview: Disney's 3D guru

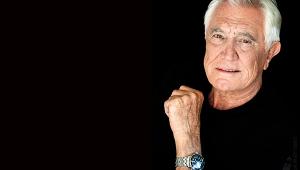

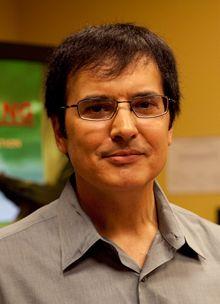

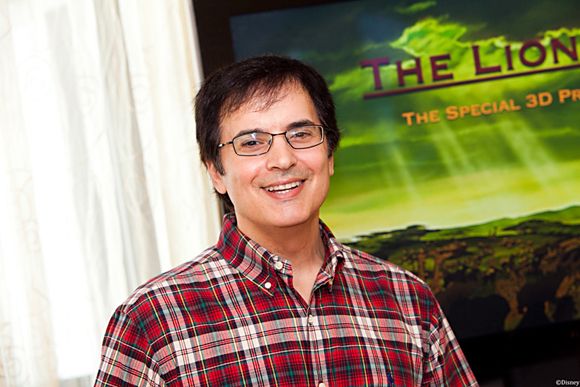

Now, with the ret-conned movie out on Blu-ray, Ali Upham caught up with stereoscopic supervisor Rob Neuman to talk about the transformation of this animated classic into one of 2010's biggest 3D blockbusters.

When did start work on the 3D conversion for The Lion King?

'About a year ago. There was some pre-production work where we were defining the tools we needed. In-house we have software developers, so I came on to work with our technology department and say what kind of tools we would need to do this. That was the initial thing. When you’re tackling a project like The Lion King, which is by all measures a classic, when you’re approaching something like that it’s nice that we had the original filmmakers on hand. We’d watch the movie a couple of times, once with the sound down so we could discuss what the big moments were and what they really wanted to hit hard, and what their feelings were about the use of 3D. For tackling a work of this stature it was critical.'

How long did the whole project take?

'It was a four month process. About 60 artists working for about four months.'

Can you talk us through the conversion process?

'When we first began the process of taking traditional animated content and putting that into 3D it was something that really hadn’t been done before, and it has its own specific challenges. From a technical standpoint there were some advantages. It’s a relatively modern film – back when they did this it was one of the earlier films that Disney had made using this system that it built called CAPS, which was the original digital ink and paint system. It was very pioneering thing on Disney’s part, up until that point animation had been done by taking cels and photographing them with the camera, so instead the artwork was scanned and then put through the the CAPS system which allowed them to do the ink and paint and the photography. And so one of the first things we had to do was we had to task our software developers with taking this stuff – 1994 was a lifetime ago in terms of technology – take this stuff and put it into a format that modern compositing programmes can work with.

'Before approaching this film I’d worked on several CG stereoscopic films. Having set up literally thousands of shots in 3D using cameras it gave me the ability to look at a shot and say how far in terms of describing – and we describe parallax in terms of pixel offset relative to the resolution of the image – how on a 2K image and between the left and right eye an object is going to be displaced so far. So it gave me the ability to look, after setting up so many shots, at a scene and know exactly how many pixels offset I wanted it to be at.

'After we do that the next step was to go through every shot, something in the order of 1200 shots. If it was a relatively simple shot where you just have characters and a static camera I could get away with drawing my annotations on one frame. If it has more complex blocking or camera work then I have to go and do multiple frames. So this was going through and putting all these little benchmarks in, describing where everything needed to be inside stereoscopic space.

'One of the beautiful things about the fact that we had this film digitally archived is that we had all of the original artwork levels [Backgrounds]. A big advantage over a live action movie that gets converted is that you don’t have all this background, you wind up with areas of disclusion between the characters and the background which we didn’t have to deal with.'

How do you bring character to life?

'When you’re dimensionalising a character the very base coat of depth we give them is this gradient algorithm approach, character inflation we call it. It would be analogous to if we were to take a shape of Mufasa and if we were to make a picture of a Mylar balloon cut out in that shape, this is putting the air in that Mylar balloon, so what you wind up with is a kind of puffy version of it, but it doesn’t have any articulate depth, so you wouldn’t have the sense of his leading leg being in front of his trailing leg, or his front quarters being close than his hind quarters, so none of that would be available. So this is giving him his puffy quality, which is one step closer to being realistic.

'Then we add structure to it. For example if you look at the lion’s head, any face, there’s a cubic structure to it: we have cheek plains, we have a plain in the front of our head. Things like a muzzle or a nose have more of an ellipsoidal quality. Then for legs and tails, we had joint tools. This would allow us to swing it all the way forward and all the back and give us a degree of control over that.

'We also add an intelligent depth painting method. All the artists had to do was go in and do little strokes of grayscale that correspond to the black points being furthest back, the white points being furthest forward, and as you add little hints the resulting image starts to look more like the relief map of a lion. This was an incredible time-saver.'

What were the biggest challenges of the 3D conversion?

'In general there’s a certain artistic challenge that hasn’t been met yet by 3D films that you see which is using depth as a filmmaking tool, as something that’s supporting the narrative, I tend to see either two things: there’s an approach where you’re just strictly taking it as a documentary style usage of it where you are just trying to use a defacto placement. Or then there’s the gimmicky approach where you are just strictly trying to see how much stuff you can make fly out of the screen, and neither of those really have to do with what the narrative of the film is. That’s why I think the challenge of the 3D filmmaking community is to step up and really use it as a storytelling tool.

'One of the challenges in terms of using 3D artistically is to maintain a sense of scale and the correct point of view. You have all these great shots in the opening sequence of the savannah, of Africa, which is a character in itself, but you have to have the sense of scope and grandeur. What you see a lot of stereographers do, if they have the ability to put depth into something they will put depth into it, but that has a miniaturising effect. You have to have the appropriate sense of scale – something that has grandeur can’t have an immense amount of stereoscopic depth, it has to be relatively shallow but placed at the correct distance.

'And then technically the big challenge of this film was that we were dealing with characters who are quadrupeds. With a quadruped, it’s extruded much more into space. It requires much more of that specific detailed work in order to make sure you have a character that’s living in this three dimensional space. Also it complicates the interaction of the character and the environment. You have to maintain ground contact with your character, you have these immense backgrounds that are spanning all this depth and the character has to be living in that. With a human or a biped character you are almost at a single point of contact in space, with a quadruped you have these four spots that are radically different in terms of where they are located in space and you have to maintain that contact.'

When you reviewed the film were there points where you wanted to embellish the 3D further, or pull it back?

'It’s usually pulling back because as someone making a 3D film your task is to add that dimension and kind of maturity that you have to exercise is pulling back from that.'

How has 3D changed the animation industry?

'The Lion King was a case of a legacy film that we’re going back into, but in the case of a new film that’s being made with the knowledge that it’s going to out into 3D cinemas I’d still say that except for these moments that are real 3D moments, filmmakers aren’t thinking about it specifically. In a live action film the choice of lens can make it almost impossible to get a good 3D result, but in our CG films we’ve developed a tool set that allows filmmakers to do things the way they have been doing and not have to think about it, and still get a great result.

'I would say 3D hasn’t had a huge impact on the filmmakers process other than they know when they are creating certain moments they know that its going to be a great 3D moment that will really sing when we put it into a 3D cinema.'

What does the future hold for 3D?

'From a technological standpoint I think the inevitable thing is it’s going to move to is glasses free. Once that’s in a mature enough state that it can give a great viewing experience. Right now on larger screens it’s more of a gimmick. It works fairly well on handheld devices because you only need to create a single viewing point and the viewer is in total control of where the device is placed relative to their eyes so you get a good result from that. Also by creating a single viewpoint you aren’t dividing down the inherent resolution of the device. Those are already fairly successful I think. I think we’ll see the technology mature to the point where larger screens can begin to enjoy that, that will make it a better experience.'

How have film fans responded to 3D and why does 3D Blu-ray matter?

'Essentially, for the last century filmmakers have been making films that really are 3D and they are capturing a 3D world. They are trying to present depth to the best of their ability to the public, through a flat projection mostly, and they’ve developed a bunch of cinematic tricks that make things feel inherently more dimensional. So now we have a way of taking that and putting it into a real physical framework of depth. But what happens is, the magical thing about 3D is once you supply these two separate views to your eyes it kind of triggers that part of that visual cortex and magically you’re sort of saying OK, you’re responding to something that isn’t just flickering lights on a wall, you’re responding to it as if it is part of your environment and that just makes it more engaging.

'If its done wrong it can pull you out of it and at worst it can be uncomfortable, but if its done right, well here’s the testament to it and that’s what’s really gratifying when I do my job: when I go and create the 3D version of the film and I go back and look at the 2D, even though I think it was a great film I feel like something is missing from it. You’re just looking at it and something’s not right. It’s lacking something. As long as filmmakers can create something where that’s the effect then essentially what they are doing is creating something that’s more engaging. There’s more neurons firing, you’re being lured into the story more, but essentially the story has to be there. The same elements that are attracting you to the story but its keeping you that much engaged.'

Can we expect more Disney classics in 3D?

'We’ve developed this technology and we’re incredibly happy with the results we’re getting but in terms of our current business model at Disney animation is more geared towards making new content. The incredible talent that we’re able to utilise on this, the 60 some-odd artists drawn from different departments of filmmakers in animation, who are normally busy making our new content, we were lucky to get them in between productions. In the foreseeable future we are going to be stepping up to a new release a year, which means less time in between productions. I’m not sure when the next opportunity will be but we’re looking forward to it [Since this interview, Disney has confirmed three more 3D re-releases - Finding Nemo, Monsters, Inc. and The Little Mermaid].'

What’s your favourite moment in the new 3D version?

'There are so many great moments. It goes back to the opening sequence, the circle of life, after watching that, and we’d been working so intently on every shot that finally when we put the entire sequence together to play it in continuity, and went through it... then boom! The title comes on, the hairs were standing up on the back of my neck. Everybody in the theatre you could tell was just electrified by it.'

The Lion King 3D is available to buy now on Blu-ray from Walt Disney Home Entertainment. This interview first appeared in the January 2012 issue of Home Cinema Choice.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|