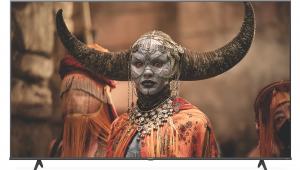

Interview: Richard Stanley on cult horror Color Out of Space, his love of H.P. Lovecraft, and working with Nic Cage and alpacas...

You've described yourself as a ‘lifelong Lovecraft fan’. When did you first come across his work?

I guess when I was around seven or eight years old, because he was my mother’s favourite author. So my mother, crazily, read me some Lovecraft stories, starting with the lighter fantasy material. Then, by the time I was 13, I was already a nerdy 13-year-old that had read all of the Lovecraft canon and knew all about The Call of Cthulhu.

What was it about his writing that struck you?

Something in Lovecraft’s anti-human worldview and the notion of the world being one level of a multi-dimensional universe, I guess, caught my interest, even as a teenager. I know a lot of it bled across into my attempts at creative writing at the time. It gave my teachers a very hard time as I was using strange words and phrases like 'Non-Euclidean geometry'

in my school essays.

His work remains influential today in cinema. What makes it resonate strongly with modern audiences?

I think it’s much easier to understand today. At least the concepts are; the language may be harder for people to come to terms with, because it’s still written in a very long-winded, old-fashioned

style. But, so many of those concepts, like the aforementioned Non-Euclidean geometry, which didn’t exist in Lovecraft’s time... since then we’ve had Benoit Mandelbrot’s discovery of fractal geometry, and chaos science, and a whole bunch of ideas that have brought some of that material closer to real life than it might have been in 1926.

I hate to say it, but it may also be to do with a growing lack of faith in the idea there’s an all-wise, all-kind creator-God responsible for events on Earth. And as we step away from orthodox religion, people tend to naturally ask 'What is going on then? What actually created us? How did we get here?' And Lovecraft proposes a dark and implacable universe.

Yours isn’t the first screen version of The Colour Out of Space. Why

is this particular story so ripe for adaptation?

I think because of its setting. The Colour Out of Space is set on a farm in the New England backwoods and largely concerns one family and their neighbours, as opposed to being set on Pluto or at the bottom of the Mariana Trench. So The Colour…, I guess, presents itself to low- and medium-budget filmmakers because you’ve got a faint chance of actually being able to approximate it on screen.

Do you have a favourite out of any of those previous adaptations?

I think the most recent one: Die Farbe [2010], which is a German adaptation, sadly in black-and-white and German, which prevented it from reaching a wider audience. It’s a very interesting retelling of the story. It makes a couple of interesting leaps.

And shooting in black-and-white means not having to worry about creating an alien colour never seen on this planet before...

Yeah, I think that was part of the idea! It unfortunately mitigates against the film slightly, because it’s very difficult to get modern American teenagers to strap down for a subtitled, black-and-white German film.

Your project was first discussed some time ago. How difficult was

it getting it up and running?

It certainly presented obstacles. The main one of which is that it’s a reasonably faithful adaptation of the story, which means that it doesn’t conform to the current template of what they call 'save the cat' in Hollywood; a three-act structure with redemptive arcs for the characters. In a Lovecraft story the only ways out are death or madness.

Agents and managers tend to look for somewhat more positive arcs when they are searching for vehicle parts for their actors. So trying to find a lead actor to actually drive the project took a few years, just trying to get the script into the right hands.

What was it like adapting the short story for a feature-length film?

A big challenge came from updating it and dragging it forward into the present day or near-future, which felt like a necessary thing simply because I wanted to make the Lovecraftian threat, the Old Ones [ancient alien deities present throughout Lovecraft’s writing], into a clear and present danger. And that meant having to deal with issues like how come the family don’t just call an Uber and get the hell out of there.

Also, Lovecraft’s technique, his anti-humanism, his lack of interest in human emotions, means that there are a lot of distancing mechanisms in the text where we’re almost inside a flashback inside a flashback. The principle dramatic events of the story happen at such a remove to the narrator that on a first reading you can almost miss they happened at all. The biggest dramatic events of the story are dismissed in one or two sentences. There are a lot of important details that are just implied and then he spends two paragraphs talking about the trees!

Is it good to be back making

a fiction film?

Well, I have to say that returning to making a dramatic feature film, particularly making a sci-fi-horror movie like Color Out of Space, was an absolute joy. It made me sorry that I hadn’t done it years earlier, because I do feel like I have a certain proclivity for the genre, and after two or three days

it just came naturally. For me it was an intensely enjoyable experience.

The process itself has hardly changed. The only difference now, in terms of having video technology, is that we can shoot in lower light conditions, and the camera operator doesn’t say 'Speed' any more when you say 'Roll camera', they say 'Frame'. Otherwise the process pretty much rolls the same way. It’s great, however, to watch your take pretty much instantly and have a full idea of what you’re getting in the can, instead of having to wait 48 hours for rushes.

The downside is that everyone who financed the film and everyone responsible is looking over your shoulder and they’re all seeing your footage as you’re shooting it. Which means you can’t hide anything. Any deviation from the script or crazy improv immediately becomes common knowledge.

In one particular case Nic [Cage] did a headstand during a take. I recall when this happened the First Assistant Director looking at me like 'Should we cut?' and it’s like, 'No, let’s roll a bit'. But that didn’t play with some people and didn’t make it into the film.

Have modern technologies made

it any easier to realise Lovecraft’s ‘unspeakable’ horrors onscreen?

It’s certainly opened up a bunch of doors, in terms of visual effects work, in that we’re now able to airbrush our physical effects and improve what we’re doing. Which does make tentacles and this kid of organic horror that we’re doing a little bit easier. We were also using a lot of fractals, fractal geometry, in the animation. I was very intrigued at how we were able to take something that didn’t exist in Lovecraft’s time, like fractal geometry, and bend it into serving his weird stories. It seemed like a good fit. I was very, very happy with the material contributed by User T-38, the Spanish VFX crowd, which I think saved us over and over again during the course of the shoot.

You’ve not always had the smoothest of rides with production companies. What was SpectreVision like to work with?

Well, I will say in Spectre…’s favour, this was the smoothest filmmaking experience I’ve ever been involved with and the closest transition from page-to-screen of any screenplay that I’ve written. The completed movie bares a stronger resemblance to the original script than anything else I’ve worked on. And once they got behind the basic vision, they really stuck to their guns. They understood that there were certain things that we couldn’t change about the material. They knew the film would have to lurch over the edge into this place of complete maddening psychedelic chaos in the last reel. And they were super supportive in that.

How important was Nic Cage in getting Color Out of Space made?

The script would have remained on the shelf had he not picked it out of the pile. I think he at least had the guts to take on a part that was this weird and this creepy and this far away from normal romantic lead or action hero roles.

His character is a flawed, weak man incapable of dealing with the problem they are facing; who simply cracks and falls apart under the pressure. And I think it was super of Nic to take that on. There are a lot of moments in the film where we feel that his identity is gradually crumbling. So I was very happy to have him there.

Also, he shares a similar sense of humour to myself. There’s a persistent kind of black comedy to what he’s doing, which is a very good match to what I’m doing. His timing is spot-on. He also brought so much positivity to the set that whenever he was there the whole cast and the crew were really on point. Generally, we got all of his scenes in two or three takes, very fast, and as a result we discovered we were running ahead of schedule, which is something that’s never really happened to me before. I’m used to leading men slowing me down and having the opposite effect on shooting.

Particularly after The Island of Dr. Moreau, where something like 40 main unit days were lost thanks to cast members not coming out of their trailers, it was wonderful having a collaborator, a leading man who was actually putting all of their energy into the right place.

I’m also amazed that he’s practically making one movie every three months at the moment. The man has incredible reserves of energy. Whereas after Color… I had to take a couple of months off just to recharge.

You're working on further Lovecraft adaptations – which stories are you looking at?

The notion was always to go after the core canon

of stories, the most important Lovecraft stories.

All are in public domain, so I can’t tell you what

we’re aiming at on the third one; it’s too far down

the track and if I have to say where we’re going, within three or four years it’s possible there might be eight other adaptations, two from The Asylum. So I’m going to keep quiet about what we’ve got in mind for number three.

But I can say that number two will be The Dunwich Horror, one of the most popular H. P. Lovecraft stories.

Will it be more faithful to the source material than previous screen adaptations?

Yeah, again it’s been poorly serviced. Much as I’m fond of Dean Stockwell [star of 1970's The Dunwich Horror], the previous two adaptations missed by a mile. I think there’s huge amounts of room to move

in there, particularly with the ultra-dimensional Whateley family. The notion of a bunch of dispossessed, backwoods hicks who have crossbred with ultra-dimensional demons is so good that it’s kind of unmissable.

Coming back to Color Out of Space, let's talk alpacas. Where did the idea come from for having them in the film – and what were they like to work with?

The idea sprang out of updating the material and trying to make it somewhat different from what people were expecting. I thought, we can’t have a family with a cow and a chicken and a pig; I wanted to make the family into a 21st century family who have come out of the city or suburbia, bought a farmhouse, but don’t really know what they’re doing. As in a lot of people I’ve come across in real life,

who retire to the country and buy a big spread. They usually have some crazy scheme where they think they’re going to make their own wine, they’re going to have their own brewery, they’re going to raise angora goats and make angora sweaters – which

is usually inappropriate for the environmental circumstances they end up dealing with. So that

was part of the thinking.

I also wanted to use an animal that hadn’t really been on screen before. If we were going to have mutating farm animals, I thought let’s have something which the audience hasn’t already seen. It came down to a toss-up between alpacas and ostriches. The thinking at the end of the day was that ostriches were a bit more dangerous to deal with and kick real hard. Whereas alpacas are calm, serene, benign and clean animals that are actually very user-friendly to work around.

Our central alpaca team were very stoic. The only problem was that it was impossible to scare them in any way. We couldn’t get them to act tormented. None of us knew what an alpaca scream sounded like, and as none of us were prepared to traumatise the alpacas to record it. We basically had to come up with it in post-production and find a number of different sound effects to splice together to try and make it sound like alpacas...

Lovecraft’s story deals with ‘globules of colour’ that fall outside anything known in the visible spectrum – which could obviously cause some problems when it comes to depicting that onscreen...

Well, that’s one of the biggest challenges. It’s implied by the title already. I think it’s one of the reasons the previous adaptations didn’t keep the title. How do you show a colour out of space, from beyond the human spectrum? It’s obviously a scientific impossibility onscreen.

So instead I applied a lot of mad science to it and figured, okay the human visual range basically sits between ultraviolet on the one end and infrared on the other. Just like our auditory range sits between ultrasound on the one end and infrasound on the other. When something dips out of our auditory range it’s gonna have to go either down through a deep bass into something we can hardly hear, or into a high-pitched screaming whine that then literally goes out of our perception. So I figured we could sort of see the fingerprints of the colour, even if we couldn’t see the creature itself. This took us towards ultraviolet and infrared – and magenta is kind of what you get if you cross the two.

We were constantly pushing towards the outer limits of what humans could sense. I think this works particularly well in the soundtrack, where the sound design keeps pushing into ultrasound and infrasound, particularly towards the end of the movie. This was something Colin Stetson, the composer, really ran with. It’s something that helps the sense that something is really stretching our consciousness or that our perception is being besieged by something which we can’t openly perceive.

Some of this creeps into Annihilation [Alex Garland's 2018 sci-fi] as well; it uses some of the same colour palette. Annihilation came out about six months before we started work on Color Out of Space and all of us did a big double-take and then decided to proceed down the same path and not change anything. There was a last-minute, 'Shouldn’t we change to an emerald-green or psychedelic turquoise?' but then it just seemed like a good idea to stick to our guns and keep going because there is some basis in actual mad science, or fringe science, in there.

We’ve touched on some of the other Lovecraft adaptations, but have you had any real favourites among those that came before?

Weirdly, the most Lovecraftian films I can think of, the most Lovecraftian moments, usually happen

in non-Lovecraft adaptations. Like in films which aren’t direct adaptations of his work, like the aforementioned Annihilation, which is a cross between The Colour Out of Space and the Andrei Tarkovsky movie Stalker [1979] and the source material in particular, Roadside Picnic.

The most Lovecraftian monster of all-time is ‘the Thing’ in the John Carpenter movie of the same name [1982]. And the Carpenter movie has a truly Lovecraftian point of view which embraces the dehumanisation of the characters and has an extremely negative ending. If only it was a Lovecraft adaptation and not from a John W. Campbell story it would probably stand as the best Lovecraft movie ever.

You’ve been linked to quite a few films over the past few decades that never came to fruition – Vacation, The Bones of the Earth,

a Hardware sequel. Do you consider them all dead now?

No, most of them are still alive in some kind of

weird way. There’s still electro-chemical activity going on in their brain-stems. I would love to see

an official Hardware sequel/reboot made. Mostly because the idea is still current. The use of drones

as an instrument of state policy and authoritarian control over people is still super strong. I would like very much to see a cyborg movie where the creatures are not out-of-control or trying to take over the world like Skynet, but are actually fully-functional and acting as an extension of state

policy as they’re supposed to do. It’s something that I haven’t really seen in a movie, which I’d still like

to try and address.

The problem with Hardware [pictured below] is the rights are so desperately messed up and divided between all the different companies that broke up Palace Pictures back in the day. We haven’t been able to get all of the rights into one bag to actually go ahead and make the movie. Which has kept that script, and kept Hardware, in a kind of eddy where we just can’t move it forward. But I love the material and would dearly like to return to dystopian cyberpunk sci-fi right now if I had the option.

Have you ever considered a return to The Island of Dr. Moreau, given that it was such a passion project of yours?

It's such a vast project, it’s such a monster,

involving creating a new island, rebuilding Moreau’s compound, redesigning all of the beast-people,

that it’s a considerable thing to take on. And it has

at its heart an idea that’s so horrible, that people

are still wary of it. Human-animal hybridisation

still presents such ghastly ethical issues that people

are naturally scared of it. Earlier this year we saw the shock-horror reaction to Cats; there’s just something about crossing your human cast members with animals and having them behave like cats that just freaks out people. Plus hair and fur is one of the most difficult things you can get at with VFX. So it presents big challenges.

The thing isn’t dead, though. At the moment it’s being developed as a six-part television series. Whether the folk involved are crazy enough to go down that route remains to be seen, but I’ve written a one-hour pilot and a series bible which is currently out doing the rounds.

You can’t honestly crush that story into one movie. One of the many things that went wrong with the previous adaptation was there’s simply too much going on in H. G. Wells’ head to concertina all the ideas into 110 minutes. An expanded …Moreau would give you not only the information on the island when the castaway arrives, but would give you the chance to show you how the island arose – because Wells does that all in flashback in the book. It gets to about halfway through the book and suddenly Dr. Moreau sits down and spends an entire chapter explaining how it all happened, which would make for a whole season of a TV show if one had to adapt it. The temptation to run on and show what happened to the beast-people after the book’s end is also very, very tantalising. So, yeah, that material seems to lend itself to that sort of thing.

You’ve been involved in revisiting your earlier films on disc for new commentaries and other bonus material. Are you a fan of extra features in general and what do

you think they can add?

Yeah, I am. I think that, particularly, if we’re moving into an ecology where most people are going to

be owning these movies and having them on their shelves – because we can’t trust streaming: such

a tiny amount of material is actually available on streaming platforms that if you’re going to be serious about cinema we’re pretty much in a situation where you have to buy films and have them on your shelves – it always feels to me that I want something extra

to make the package special.

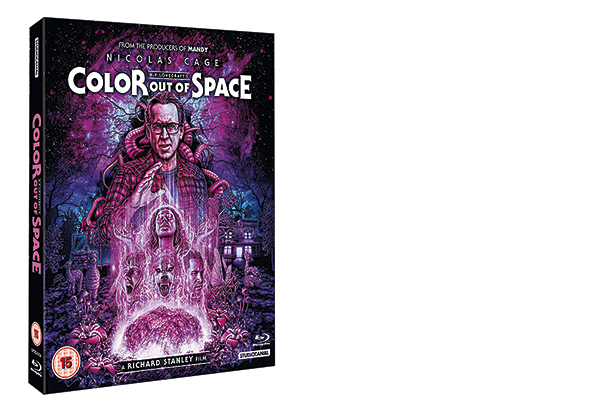

And we’re in a situation where all the material that I’m forced to cut out by the front of house, the distributors, can live as deleted scenes on Blu-ray and DVD. I fought pretty hard to make certain that Color Out of Space has the deleted scenes from the movie. Unfortunately, right now, they weren’t included on the UK release, but have been included on the Australian and German releases. Which cheers me up because they’re often sequences that we put a lot of work into, but which ended up being dropped, usually for pacing reasons.

Do you enjoy watching movies at home or, prior to what is happening now, was going to the cinema still your preferred way of interacting with them?

Sadly, I think that going to the cinema is still the best way of engaging with a film like Color Out of Space;

a film that is very heavily involved in the audience reaction. I like things that increasingly build some kind of hysterical momentum. I do like it when audiences shout back at the screen, or react in some way. I hate it when people are just sitting still in their seats and are inflexible.

I was very much enjoying the way that Color… was just getting its legs before the pandemic came along and shut us down. People were coming back for second or third screenings, [had] figured out that the film was a good time. I like to think I mix up a certain amount of 'yuck!' with my 'boo!', try to chop it up at a reasonable pace. And that’s an experience that’s difficult to have on your own. It’s really good to have the audience reaction in there.

Color Out of Space is out now on Blu-ray, DVD and Digital, courtesy of Studiocanal

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|