Gone but not forgotten: remembering some of home cinema's best (and worst) innovations

Toshiba ZL2 – a 3D TV without spex appeal

'This TV will rightly be looked back on in the years to come as the start of a new era in television technology.' So said HCC's John Archer in his review of Toshiba's ZL2 TV in the Summer of 2012. Yet he was referring to this 55in LCD screen's 4K pixel count, not its glasses-free 3D playback talents. Both of these tech tricks were world's firsts.

The 3D TV revolution was in full swing in 2012, complete with discussions about active and passive technology, lamentations about crosstalk noise and the cost of 3D spex, and wondering when James Cameron's format-defining Avatar would finally get a wide 3D Blu-ray release.

And amongst all this, the idea of autostereoscopic displays, requiring no goggles to view 3D images, burbled away in the background.

Enter Toshiba with its ZL2, a 'glasses-free 3D' set carrying a £7,000 price tag. It used an array of lenticular lenses to direct picture information to your left and right eyes, which your brain would then collate into a single 3D picture. Nor was it just for one viewer – Toshiba claimed it could accommodate up to nine pairs of peepers, using face recognition technology via an in-built camera, plus the company's CEVO Engine processing, to target its 3D 'sweetspots.'

To make sure the 3D image wasn't a blocky, low-resolution mess caused by all those filters, the ZL2 used a 4K panel. This was arguably its more exciting element, particularly once you discovered the glasses-free 3D presentation was dependent on you keeping your head still. Yet Toshiba scored an own goal by not enabling a native 4K video source to be input by HDMI (you could view 4K JPEGs from USB), so all buyers could do (if there were any...) was take advantage of its HD-to-4K upscaling. Here the ZL2 was impressive, and gave a taste of things to come.

As for spex-free 3D, we came, we saw, we shrugged.

LG Super Multi Blue – a format war fix

LG's BH100 'Super Multi Blue' disc player landed in 2007 as the AV equivalent of a bottle of combined shampoo and conditioner. The South Korean company had cast an eye over the fractious HD DVD vs Blu-ray format war that had been raging for a year and decided that a machine that could handle both types of disc was in order.

It even launched a successor – the 'Super Blu' BH200 [pictured] – at the 2008 CES. Unfortunately, during the same show, Warner Bros. announced it was withdrawing support for HD DVD, leaving the format effectively dead by the time that new double-duty deck hit shops.

Still, LG's combi machines looked like a good idea on paper, especially to film fans who felt forced to either stick with one format or buy two separate players. Nor were they prohibitively priced.

The problem was that both were a step or two behind the tech curve. The BH100, for example, was unable to play CDs (an odd flaw for a multi-format deck), but far worse was the hatchet job it did with HD DVDs. Although doomed to failure, HD DVD bested Blu-ray by some margin when it came to bonus features and interactive menus, something LG's deck couldn't handle at all – you just got the movie, and nothing else. And further niggles (the lack of a bitstream audio output on either model, no Ethernet connection on the BH100, various bugs) made LG's 'Super' hardware feel not so super.

TiVo – Putting the P into PVR

Sky+ may have popularised the set-top-box, but it was TiVo in 1999 that ushered in the hard drive recording revolution, finally putting an end to the videotape era. It took its time arriving in the UK – American audiences had the jump on Europe by around a year – but that didn’t diminish our excitement.

The original TiVo box, sold under the Thomson brand, ran on a 50Hz processor. A custom chip allowed TiVo to multitask, dialling in via an attached landline to refresh its programme guide while playing one stream and recording another. Shows were archived to a 40GB hard drive, enough for 40 hours of SD. Bitrates peaked at 6Mbps.

This tech spec might seem rather staid today, but the joy of TiVo was always the user experience. The recorder had personality – owning one was fun, futuristic.

Thomson gave up on TiVo quite quickly – in 2002 – but it returned to Blighty in 2010 in Virgin Media's TiVo box [pictured], complete with thumbs up/down voting and suggested recordings. The cable giant is now replacing it with its 'TV 360' UI.

CED – groovy movies

LaserDisc may have been the definitive video disc format, but CED (Capacitance Electronic Disc) was a low-cost rival that very nearly gave it a run for its money.

Unlike LaserDiscs, which like CDs were read by a laser pick-up, this all-analogue option took a leaf out of vinyl’s playbook, and read its grooved discs with a proprietary stylus. The benefit of this approach was cheap replication costs, the downside was ...well, it was a video disc that was read by a needle.

In the UK, Hitachi was CED’s greatest exponent, in the US the market was dominated by RCA's SelectaVision players. Both were cheaper to buy than rival LaserDisc systems, but gritty, low-res picture quality made CED a poor substitute.

An obvious flaw in the CED master plan was disc wear. Platters actually had a lubricated surface to reduce this, and were sold in caddys as a result. The player extracted the disc from the caddy, to prevent dirt and debris caused by handling.

CED launched with a 50-strong movie catalogue, and titles actually continued to be released several years after player production halted. These are still available on eBay if you want to own some, but we suggest you frame them rather than play them.

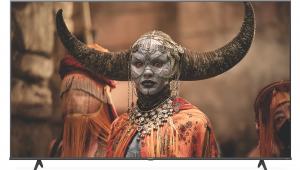

Curved TVs – home cinema gets the bends

‘Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.’ Dr. Ian Malcolm may have been lecturing Professor Hammond in Jurassic Park, but he could just as easily have been berating TV bosses about curved televisions.

After spending the best part of a decade trying to engineer the ultimate flatscreen, transitioning from fat CRTs to flat LCDs, the world’s biggest brands thought it would be a smart move to drive buyers round the bend with a new wave of curved TVs, aping the immersion of large format cinema.

There were considerable challenges. LCD backlights don’t easily bend and panels were bulky. OLED, a tad more flexible, was fragile. When wall-mounted, curved TVs looked more Pringles than Panavision.

Samsung led the way. Speaking at the brand’s product forum in 2014, president BK Yoon promised: '2014 will be the year of curved Ultra High Definition TV.' At the same event, Michael Zoller, Samsung’s sales and marketing chief, insisted that research confirmed the human eye is naturally drawn to strong curves. The TV maker also said its aim was to mirror the curvature of the human eye. All manner of hokey science was proffered to justify the effort.

Rival brands were quick to follow, but it soon became clear that glare and reflections were an issue. Where traditional flatscreens picked up one room light, a curved model picked up two. Image geometry looked odd. You could mostly get away with it on live action, but EPGs appeared wonky. The TVs also had a very narrow viewing sweetspot.

Both Samsung and LG showed prototypes that could switch from curved to flat upon demand (technically ingenious, also pointless). Soon after, despite increasingly generous promotions, sales of curved TVs flattened. Then they were gone.

CD-i – the joy of text

Released in 1990, Compact Disc-Interactive, better known as CD-i, was billed as a futuristic alternative to cartridge-based games and books. Exploiting the data capacity of CD, it was an ambitious cocktail of MPEG video, low-resolution audio and text.

Developed by Philips, its bizarre software catalogue covered everything from puzzle games to interactive encyclopaedias including The Joy of Sex. Most heinous of all, the format was also probably responsible for the term ‘infotainment’. But as CD-i discs could hold 72 minutes of MPEG video, it became an early DVD forerunner.

Philips shut down its CD-i operation in 1996. The format wasn't all bad though. It peaked with video-centric games Dragon’s Lair and Mad Dog McCree. The system’s ability to branch from one sequence to another, plus compatibility with a light gun, made these arcade recreations a hoot.

Sony XEL-1 – OLED starts small

Long before LG Display cornered the market in OLED, Sony blazed a path for the technology, convinced that its ‘organic panel’ was the future of television.

Unfortunately, it was (literally) thinking too small when it launched its 11in XEL-1 in 2007.

A black-mirrored design centrepiece, the XEL-1 astounded viewers with a wafer-thin panel that was just 3mm at its thinnest, jauntily affixed by an aluminium side arm to a tuner base complete with a Memory Stick slot and two HDMI ports. We had never seen anything quite like it; the screen appeared to be almost floating.

Much like contemporary OLEDs, the XEL-1 offered an exquisite black level performance and vibrant hues, even in scenes with low light. Screen resolution, however, was a paltry 960 x 540.

While HDR wasn’t on the agenda back then, Sony alluded to it with proprietary Super Top Emission technology, which allowed the XEL-1 display to channel peak brightness, and ‘faithfully reproduce light flow such as reflections of sunlight or camera flashlights.’ The set also boasted superior native motion clarity, but following a fast-moving tennis ball on such a diddy screen was a big ask.

Sony has probably never been so ahead of the TV curve – it just needed to go large.

Paradigm SUB2 – bonkers bass

Is it a coffee table? Is it a piece of objet d'art? No, it's a six-driver subwoofer claiming 9,000W of peak power and a 7Hz low-frequency response. Meet Paradigm's SUB2, one of the maddest subwoofers ever made.

Weighing over 100kg, and arranging its half-dozen 10in drivers within a hexagonal cabinet (part of its 'vibration-canceling design architecture'), the SUB2 was built for people who wanted premium, ultra-low bass and didn't really care how they got it. Its performance was remarkable – scarily deep and brutally loud, but speedy with it. And it came in a cherry red finish [pictured] if the black option was too terrifying for you.

Actually, this is one product that hasn't quite gone away. There are still models available, only now retailing for over £11,500, not the £7,250 launch price of 2010. So maybe grab one as an investment.

Denon's Cara S-5BD – when two became one

Back in the day – well, the 2000s – Denon was a purveyor of high-end, heavyweight DVD and Blu-ray players. Yet the brand was also known for its AV receivers, and in 2010 it decided to marry the two.

The Cara S-5BD was both disc-spinner and surround sound amplifier, the technology (including Audyssey EQ) squirrelled into a black gloss cabinet that looked positively futuristic at the time and still causes a double-take today. All you had to do was add some speakers and away you went.

So why didn't it take off? Probably because AV-hedz were happy to stick to separates (and wanted more than the five-channel power plant of the Cara) and convenience-first shoppers were put off by the £2,000 price. We wish we hadn't given our review sample back, though.

Philips 21:9 – wide-eyed TV

Before you complain about letterbox bars on your flatscreen, remember that Philips briefly tried to convince us all that the shape of things to come was 21:9. The Dutch TV giant, obviously persuaded by the preponderance of ‘Scope movies in theatres, concluded that we would all rush to buy 21:9-shaped screens in a quest for a convincing home cinema experience. It duly launched its first super-wide set in 2009.

Unfortunately for Philips most widescreen TV is formatted at 16:9, and, even worse, there were still a lot of 4:3 broadcasts during the noughties too. The result was a bit of a mess. You could choose to watch 16:9 or 4:3 natively, with black bars down the side, or make use of a range of format modes to automatically stretch the edges of non-compliant ratios to fill the wider space. Even with 21:9 movies on Blu-ray the image wasn't pixel matched, as the content was still encoded as 16:9 with top and bottom bars and therefore essentially zoomed to fill out the screen. So while the form factor was alluring, the marriage between hardware and software felt doomed to failure.

Samsung did nearly join the CinemaScope fun, previewing a humongous 21:9 105in UHD TV in 2014. But it never came to market...

Bose Solo TV – making a stand

In 2012, sonic innovator Bose launched the Solo TV. A successor to its earlier Solo soundbar, it showed off a new approach to TV audio boosting – instead of a slim 'bar, you got a deep cabinet for you to put your telly on top. The 'soundbase' was born.

In typical Bose style, the Solo TV was both forward-thinking but a little old-fashioned, offering optical, coaxial and analogue phono inputs when many rivals were embracing HDMI, Bluetooth and USB. But once you'd accepted that the only real way to connect it was to run everything through your TV first (an idea that hasn't gone away), the sound quality from this soundbase was rock-solid, with the extra enclosure space used to accommodate bass drivers in lieu of an outboard subwoofer.

Over the following years there was something of a soundbase boom, until TV screen sizes exceeded the point where mounting one on top of anything other than a full-size cabinet made much sense.

But the Solo TV certainly had more of an impact than Bose's VideoWave (launched the same year), a chunky 55in LCD TV with a six-woofer, ported bass system and eight-driver speaker array. In an era of thinscreens, it looked positively old-fashioned.

Sony HT-IS100 – anyone for golf?

Sony took the sub/sat 5.1 system concept to extremes when it debuted the HT-IS100 in 2008. This £400 bundle of fun partnered a ported sub (featuring both 4.75in and 6.25in woofers) with five almost comically tiny single-driver speakers that you could dot around your room – or wall-mount using supplied brackets – for fuss-free surround sound.

Multichannel amplification was tucked inside the subwoofer, as well as a surprisingly wide-ranging set of connections, include three-in, one-out HDMI switching, banks of component and digital optical ports, and Sony's now discontinued proprietary Digital Media Port hookup for adding iPod dock and Bluetooth adapter accessories. The sub even incorporated an FM/AM radio tuner.

The golf ball-sized speakers and fixed 800Hz crossover between woofer and satellites didn't inspire confidence in performance, but the HT-IS100 actually sounded ...not bad. But the fact Sony recommended taping or clamping speaker wires, so they didn't pull the dinky, lightweight satellites over, showed it had probably gone a step too far in pursuit of stealth home cinema.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|