DTS:X – we go behind the scenes with DTS

Once again, film fans find themselves in the midst of an audio format war. Long-time rivals Dolby and DTS are slugging it out in both commercial theatres and home cinemas with new object-based sound systems. Dolby's Atmos format matured first, launching at multiplexes in 2012 and in home setups two years later. Now, though, DTS:X is hoping to steal its thunder.

I'm at the impressive DTS headquarters and research laboratories in Calabasas, California, a city just off Route 101 as it snakes westwards out of Los Angeles. Jordan Miller, director, global communications, greets me in the company’s clean, white, super-stylish lobby, and leads me through a maze of corridors and open-plan cubicles to the company’s hallowed ‘Listening Room’. Once there, in come David McIntyre, vice president, corporate strategy and development, Dave Casey, senior director, product development, Fred Maher, audio testing and mixing specialist, and vice president of cinema initiatives, Bill Neighbors. For my visit, DTS:X is high on the agenda, but first, a quick recap...

A different approachLike Dolby, DTS pioneers digital surround sound technologies for theatrical and domestic media playback, but the approach to, and application of, its suite of products and licences was – and is – quite different to those of its competitors. Indeed, the idea of shipping a ‘double inventory’ of 35mm film prints and CD-Rom discs to cinemas all over the world in 1993 seemed counter-intuitive at the time. But it was the robustness and economy of the system that saw it adopted on a massive scale theatrically, and led to a consumer brand recognition that only a few betting men would have predicted at the time. Roll forward to the noughties and the introduction of DTS-HD Master Audio on Blu-ray and, now in 2015, DTS:X next-gen audio for cinema and home, and you have a picture of a company that is firmly riveted to the leading edge of acoustic innovation.

‘The Jurassic Era’ is how Neighbors fondly refers to the formative phase of DTS. It was July 11, 1993, when DTS 5.1 digital sound thundered into cinemas with the release of Jurassic Park. ‘It was a big deal,’ reveals Neighbors. ‘People would wait until, say, 10pm to see the film in the DTS screen.’

The opening of Jurassic Park was big, to say the least. Installations topped out at 867 screens on the opening night. ‘After two years or so, the worldwide footprint of all the other three competitors combined was 250 screens,' says Neighbors. 'Because of the approach that we had taken with the dual inventory and CD-Rom, the promise was that this was affordable and easily installed into theatres.’ But it wasn’t all plain sailing at first for this relatively small, new-kid-on-the-block company: ‘We were scrambling to ship our American-made product into Europe. We didn’t have a European address, and everything else. We were making it up as we went along. We originally set up an office in Belgium for distribution inside Europe, but then we moved to Twyford, Berkshire in the UK, until we divested that division.’

Audio geeks will now recognise Twyford as the home of Datasat. Bill explains that the advent of digital cinema – the shift away from analogue 35mm film to digital files played out on 2K and 4K projectors – meant that the requirement for a proprietary compressed audio format was no longer relevant in cinemas. The industry shifted to the use of uncompressed PCM 5.1 audio. DTS was, after all, predominantly a technology licensing business, and not a hardware manufacturer. ‘When we saw [digital cinema] coming down the pipe, the non-cinema related businesses were doing quite well; the licensing businesses and our patent portfolios weregrowing. So we divested the (cinema) company and Datasat purchased it. They were actually still delivering CD-Rom discs to cinemas until July of this year!’

Adds David McIntyre: ‘A format went away, and it really shifted the digital cinema business to being about playback hardware. We’ve never been a hardware or equipment company. For us, hardware tools are more of a means to an end to deliver an experience, which fundamentally comes from algorithms in the form of codecs. The real key was that shift to uncompressed audio – not ‘owned’ by anybody.’

In 2009, the hot buzz in the industry turned to object-based and immersive audio. As McIntyre explains, DTS reached out to SRS and subsequently acquired the company, primarily for its post-processing business, but also for its ‘funny little project’ known as MDA, or Multi Dimensional Audio. MDA promoted object-based audio in any theatrical or home application, and the DTS team knew the market was ready. ‘Our traditional place in the audio chain, for at the least the last ten years, has been home or consumer delivery, whether it’s on a disc, or a stream or a broadcast. What became apparent very quickly though was that ProTools mixers – and the entire chain in the industry – knew how to handle 5.1 or 7.1 PCM, but the moment they went to immersive audio, and the concept of objects in particular, there was no such thing as PCM anymore. It was literally undefined, and it was being left to proprietary formats. We were kind of heading back to the '90s, so to speak.’

DTS realised that its newly-acquired MDA asset included many of the building blocks which would allow PCM audio to support objects, and a ‘simple and open’ platform was created. McIntyre is keen to point out that height information has nothing to do with objects, and that the two just happened to be developed and come to market at the same time.

As object-based audio is pertinent to room layout specifically, any waveform needs to include PCM plus metadata, the latter providing time and position for any individual sound cue. A free, non-licenced ProTools plugin known as MDA Creator was also developed to give mixers and authors a chance to work without the added pressure of leasing a ‘box or engineer’. MDA is already an industry standard and is recognised by the ITU and SMPTE.

So how does DTS:X differ from competitors’ systems? Neighbors explains that cinema room speaker layout is not as stringent: ‘The MDA track gets created with an MDA Creator tool, delivered on a DCP (Digital Cinema Package), and played back in DTS:X theatres. A theatre has to have a renderer, which means it has to havean ability to read the metadata and render it. The biggest differentiation, as far as actual practicality, is that a DTS:X room has to meet certain speaker configuration guidelines on how they are installed, based on their coverage, dispersion angles and SPL, and the idea is to make sure that everything is covered.’ The in-built flexibility means that DTS:X can be easily tailored to an existing cinema’s configuration. ‘As cinemas aren’t all shaped and sized the same, this leads to a lot of economies of scale for the cinema owner,' says Neighbors. 'As long as you meet the guidelines, then you can give your room a compelling immersive experience.’

This also means that a DTS:X track can be played back in a Dolby Atmos cinema, as long as it has a DTS renderer, although Neighbors concedes that this particular situation hasn't yet arisen. Another nifty leg-up for DTS is its ability to move a single file to any room in a multiplex – whether it’s a 400- or 200-seater – as long as there is the DTS config file and renderer in the processor for each house.

At the time of writing there are currently 25 DTS:X rooms, either open or under construction, 18 of which are in North America. DTS expects to see further adoption in the UK and Europe early next year.

DTS:X will typically feature in the premium rooms in a multiplex, and the company encourages its clients

to promote the brand and its immersive sonic experience. Neighbors assumes that most exhibitors will continue to market their large format, high-octane rooms with their own in-house branding, but he recently met an exhibitor of a midsize US chain who confirmed he was ditching his own ‘silly’ label in favour of the DTS:X emblem.

Fred Maher talks me through the key setup characteristics of DTS's own listening room. Two arrays of speakers, each making up the outer sphere and inner sphere, mimic the aural credentials of both a commercial cinema room and home cinema respectively. Fifty-eight Vienna Acoustics speakers are partnered with amplifiers from Anthem, and Colorado-based Ayre. The 22.2 surround specification from Japanese broadcaster NHK, a subset of the outer sphere, acts as a basis for cinematic system monitoring, while 21 inner sphere speakers and two subwoofers comprise the home cinema system. Critical listening and codec testing are, not surprisingly, the chief purposes of this highly controlled environment.

Following an astonishing demonstration of the ‘outer sphere’ professional cinema system with a clip of Robocop from the DTS 2015 Demo Disc Blu-ray, Maher suggests we get a bit ‘nerdy’. He throws up the MDA Creator tool interface onto the screen: ‘That’s an 11.1 config file right there. You can see that each speaker has a location, an azimuth and elevation. It’s based on trigonometry. Imagine the world is a gigantic geodesic dome and the speakers are at certain points at triangulated intersections.’ McIntyre adds that ‘the point of sound is always somewhere in a triangle.’

He then demos the scalability of the content creation tool with a realistically irritating buzzing fly, as he ‘tells’ the panner that it now only has two speakers in the room. It's an impressive, intriguing demo, and I can support the affirmation that ‘the intent is well-preserved with just two speakers.’

Maher acknowledges that such a configuration would rarely exist in the real world, but the point is that the MDA file will adapt logically to the restrictions or freedoms of any given room layout. The next step is as simple as clicking a button called ‘Export MDA’. According to McIntyre, ‘That bundles up everything you had in your session into an MDA file. That MDA file can then be directly played in a DCP package.’

The conversation turns to home cinema matters, with Dave Casey picking up the baton. ‘Traditionally what would happen is this mix would go through a second revision where it’s remixed and nudged around for the home. So the creative can use that exact same MDA file and monitor it for a nearfield experience.’ A massive uncompressed MDA file is subsequently prepared for consumer distribution and ‘the output of the encoder actually creates the DTS:X bitstream that goes onto a Blu-ray disc.’

I have a DTS:X demonstration of the home system via the inner sphere of speakers using a current generation Blu-ray player. Material is also culled from the 2015 Demo Disc, with Gabriel Grapperon’s ingenious short film, Locked Up, and Run River North’s music video, Monsters Calling Home. Casey explains that the same mix will not only accommodate the current maximum of 32 speakers (as with the Trinnov pre-amp used here), but is also backwards compatible with two-year-old AVRs maxing out with 7.1, and 12-year-old AVRs with 5.1 digital surround.

The company has announced DTS:X adoption by some 20 consumer brands (including high-end marque Trinnov, picture) and, according to Casey, will ‘hit nearly 100 per cent of the market that serves the AVR/surround processor space.’ DTS:X is starting to appear on high-end models from each of those brands, and will shortly trickle down into the more attainable middle tier, with the lowest price points showing at around £500. According to McIntyre, 11.1 channels with four height speakers ‘is really more or less where people are capping out, just based on the physical realities of the home.’ Casey also stresses that the adaptability of their immersive technology is ‘less about 7.1.4, and more about 11 channels in any configuration you can come up with.’ For those who have already purchased upward-firing Atmos speakers to avoid carving holes in the ceiling, DTS is adamant that it supports ‘whatever speakers you have.’

DTS is also clear that DTS:X requires no unique AVR setup, as distinct from any other competitor’s immersive audio system. The company is ‘happy’ to talk to a manufacturer about what it thinks is best practice, but it respects and supports whatever UI is designed and applied.

Battle for Blu-rayCurrently, 94 per cent of all BD titles include DTS-HD Master Audio. When asked how DTS managed to achieve such high market penetration, McIntyre claims that there are ahost of advantages to using its codec, which relate to workflow, time, cost efficiencies and, ultimately, the strength of the DTS ‘core’. Consumers with S/PDIF-fed legacy devices enjoy the superior 1.5 megabit DTS HD core track over Dolby Digital, so ‘they get that quality difference with no end penalty when it comes to the lossless solution.’

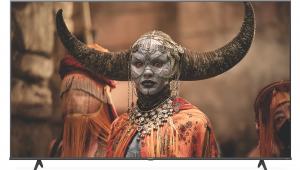

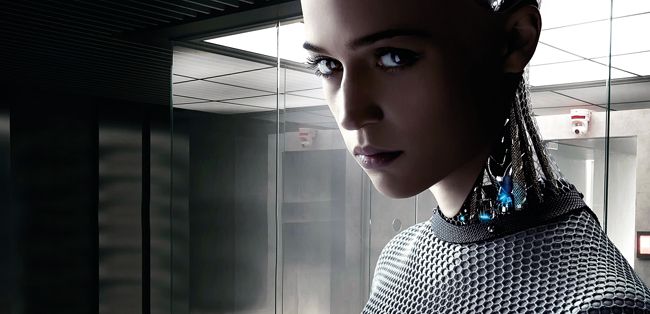

As for DTS:X titles appearing on Blu-ray, the only UK release at the time of writing is Crimson Peak, with some other titles appearing in the US (including Ex Machina, below). However, not regularly discussed or understood by consumers is the comparatively meagre amount of space available for audio even on a 50GB BD disc. And the problem is not going away with UHD BD, despite its much larger capacity. ‘Believe it or not,’ says McIntyre, ‘BD 50s for things like high-end Disney or Warner films still have space problems even for 7.1 audio. As we go to UHD BD, the first ones will be 66GB discs mostly, and so they’ve added all this video and they want to add all this audio and, yes, they’ve got 32 per cent more space, but it goes away really fast.’

Of the many media platforms that immersive audio might inhabit, I am particularly keen to find out if DTS:X music Blu-ray discs will start to appear on the web pages of our favourite online retailers. Although everyone in the room concurs that titles will emerge in the future, Jordan Miller is also quick to establish, ‘As of right now, the emphasis has been on headphone (Headphone X). There are two ways to go about it: we can create bespoke content with immersive sound in mind, or take existing audio and remix it in Headphone X.’

He expands on a fascinating project that the company pursued with the band Imagine Dragons, and its recent X-mixed album Smoke and Mirrors. On the group’s latest tour of the US, audience members were invited to observe a gallery installation with Headphone X song mixes accompanying particular pieces of art. If readers have not experienced the Headphone X demo on the www.dts.com website, I highly recommend they do so.

In the Listening Room, Fred Maher plays me the same test signal available on the website, in which an announcer’s voice informs the listener of the placement of each of 11 channels in a home cinema setup, but over the inner sphere of home speakers only. He then asks me to listen to the same test, this time with a pair of $70 headphones, and the test sounded identical. I could have sworn that the signals were still coming from the external speakers, and not from the cans. We perform the test again with a clip from the film Divergent – once again, indistinguishable results between phones off/phones on. Was DTS talking to VR (virtual reality) and AR (augmented reality) headset manufacturers? A resounding ‘yes’ on both fronts: ‘All the big players.’

Maher explains that the breakthrough with DTS Headphone X technology is achieving what he calls ‘room convolution’. Music mixes are monitored on speakers at a prescribed distance from a recording engineer, but then we listen to the same mix with headphone speakers literally right on our head. Consequently, the illusion is one of music ‘inside’ our heads, rather than ‘out there’ where it should be. He continues: ‘It’s taking the concept of binaural and making it a creative tool. Artists are going berserk for it.’ Jordan Miller adds, ‘I can literally feel the pianist is six feet away from me on the right. And then there’s a back-up singer behind the piano.’

The story arc of my DTS visit went from commercial cinema to pocket audio – it's certainly a company with ambition. But for home AV fans, all that matters is whether its DTS:X format can come to market with enough titles to make a system upgrade a no-brainer. On that, we'll have to wait and see...

This feature first appeared in HCC #254 in November 2015.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|