Moaning about movie dialogue isn't a new thing – we've been doing it since the dawn of cinema

Those with an interest in film criticism, and movie history in general, will find a lot to enjoy in new book The Times On Cinema. Edited by Brian Pendreigh, it collects nearly 100 years of cinema writing from both The Times and Sunday Times newspapers, and I've found it utterly fascinating.

Obviously, much is made of the way that opinions on movies change over time – early examples given include a 1947 review of It's A Wonderful Life ('Not a very good film') and a 1999 piece on Fight Club, which says the Edward Norton/Brad Pitt thriller 'starts out like a winner but fades fast.' I actually agree on that last one.

There's poster art to savour here, plus lengthy lists (James Bond films, cult movies) and isolated articles on everything from video nasties to the proposed plot of Gladiator 2.

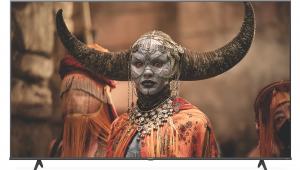

Yet where the book really tickled my fancy is the contemporary writings on The Wizard of Oz (1939), an early standard bearer for three-strip Technicolor, and The Jazz Singer (1927, pictured), the first feature-length talkie. The latter, in particular, heralded a momentous change in the nature of cinema – much more important, I'd argue, than anything that's been announced as a revolution since (3D, digital projection, D-BOX...), with the possible exception of surround sound. So what did the uncredited Times reviewer make of this new-fangled art form? They weren't keen.

Sure, the writer applauds The Jazz Singer's technological ability – 'synchronization has been almost perfectly achieved,' we're told – but follows it with gripes that will be familiar to all of us.

The Jazz Mumbler

Firstly, Al Jolson's dialogue is deemed toneless, and a 'faint parody of the human voice.' While no doubt a by-product of the delivery mechanisms of the

time (the Academy Curve, which standardised soundtracks and was designed to reduce the high-frequency harshness of the industry's mono mixes, didn't come into play for another 10 years),

it's quaint to see that people were moaning about unconvincing, unintelligible film dialogue many, many decades before the likes of Batman v Superman

and Interstellar set cinemagoers into a frenzy.

More interestingly, the Times scribe found the mere addition of (low-quality) dialogue a distraction from the onscreen action, and a detriment to the 'subtlety of acting.' It's an odd way to look at it, but I've realised I see where they are coming from. How many of your favourite movies feature dialogue-free scenes, where incessant, plot-developing chit-chat is binned in favour of letting only images (and a well-crafted soundtrack) push the story forward?

As for the colour- and SFX-rich ...Wizard of Oz, the analysis here is so wonderful that I'll repeat it in full: 'The scenery and dresses are designed with no more taste than is commonly used in the decoration of a night-club. The film is, no doubt, a triumph of technical dexterity and especially of skill in colour photography, but what is the use of making a hollyhock out of cellophane, painting it an ugly colour, and then photographing it with complete accuracy?'

Well, quite. I'd never before considered MGM's fantasy epic as a gaudy exercise in OTT movie-making, whose story is ruined by a director (actually, five of them) more interested in showing off the tech toys of the day, but now I'll always think of it as a precursor to Avatar.

|

Home Cinema Choice #351 is on sale now, featuring: Samsung S95D flagship OLED TV; Ascendo loudspeakers; Pioneer VSA-LX805 AV receiver; UST projector roundup; 2024’s summer movies; Conan 4K; and more

|